Hypothesis Testing

library(tidyverse)

library(openxlsx)

library(kableExtra)

library(scales)

library(numform)

library(flextable)

options(scipen = 999)Handout 09

Date: 2022-11-27

Topic: Hypothesis Testing

Literature

Handout

Ismay & Kim (2022) Chapter

Testing of hypotheses: the concepts

Introduction: example of formulating a research hypothesis

As part of a research on the economic effects of the outcome of the

Brexit referendum in June 2016 the effect on house values in London is

investigated. Because of the outcome of the Brexit referendum, the

values of houses in London are expected to decrease. This is especially

the case in the central districts of London, e.g. the City of

Westminster district.

A sub research question is: what is the effect of the Brexit referendum

on house values in the City of Westminster district in London.

To investigate the effect of the Brexit referendum on the values of

houses in the City of the Westminster district, a comparison is made

between the values in January 2016 and the values in January 2017,

i.e. a half year before and a half year after the referendum.

As a measurement for the value of the houses, the selling prices of

houses sold are used as an indicator. This means that the houses sold

are considered to be a random sample of all houses in this district. Due

to the outcome of the referendum, a decrease of the house values is

expected.

There are many ways to operationalize this assumption. E.g. compare the

average selling price in January 2016 with the average selling price in

January 2017. Another possibility, and maybe a better choice, is to use

the medians. It’s also possible to operationalize the assumption by

comparing the proportion of houses sold for which the selling price is

above 1 mln GBP. If house prices are decreasing it might be expected

that the proportion of houses for which the selling price is more than 1

mln GPB, is decreasing as well. The price paid data for houses sold are

collected from the open data at www.gov.uk. In the boxplots in Figure 1

the prices in January 2016 and January 2017 are compared. The median of

the house prices in January 2017 is lower than in January 2016, the

spread in the prices in January 2017 seems to be lower than in January

2016.

Table 2 gives an overview of some sample statistics. Indeed the average

selling price in January 2017 is less than in January 2016.

Figure 9.1 Boxplots selling prices houses (GBP) in City of Westminster district in London

hp_cow <- read.csv("Datafiles/HP_London_jan161718.csv") %>%

filter((year == 2016 | year == 2017), district == "CITY OF WESTMINSTER",

property_type != "O")

hp_cow_summary <- hp_cow %>%

group_by(year) %>%

summarize(COUNT = n(),

AVERAGE = round(mean(price_paid), -2),

MEDIAN = round(median(price_paid), -2),

SD = round(sd(price_paid),-2),

NUMBER_ABOVE_1MLN = sum(price_paid >= 1E+06),

PERC_ABOVE_1MLN = round(100*NUMBER_ABOVE_1MLN/COUNT,1))

hp_cow %>%

ggplot(aes(y= factor(year), x = price_paid)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = "royalblue") +

xlab("Price Paid in GBP") +

ylab(NULL) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = comma) +

theme_minimal() Note. A comparison is made between the selling prices in

January 2016 and in January 2017.

Note. A comparison is made between the selling prices in

January 2016 and in January 2017.

Table 9.1

Summary statistics prices houses sold in London, City of Westminster

district in January 20016 and January 2017

M2016 <- format(hp_cow_summary[[1,3]], big.mark = ",")

SD2016 <- format(hp_cow_summary[[1,4]], big.mark = ",")

M2017 <- format(hp_cow_summary[[2,3]], big.mark = ",")

SD2017 <- format(hp_cow_summary[[2,4]], big.mark = ",")

ttest <- t.test(hp_cow$price_paid[hp_cow$year == 2017 & hp_cow$property_type != "O"],

hp_cow$price_paid[hp_cow$year == 2016 & hp_cow$property_type != "O"],

alternative = "less")

tvalue <- round(ttest$statistic, 3)

pvalue <- round(ttest$p.value, 3)

names(hp_cow_summary) <- toupper(names(hp_cow_summary))

flextable::flextable(hp_cow_summary) %>%

width(j = 1:2, width = .5) %>%

width(j = 3:7, width = 1) %>%

colformat_num(j = c(1, 2, 4), digits = 0) %>%

colformat_num(j = c(3, 5), big.mark = ",", digits = 0)YEAR | COUNT | AVERAGE | MEDIAN | SD | NUMBER_ABOVE_1MLN | PERC_ABOVE_1MLN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2,016 | 333 | 1,490,100 | 999,000 | 2,042,500 | 164 | 49.2 |

2,017 | 236 | 1,478,800 | 1,087,500 | 1,394,700 | 123 | 52.1 |

Note. Average, median and standard deviation (SD) are in GB Pounds. The last column gives the percentages of properties sold with a selling price above 1 mln GPB. Underlying data are retrieved from http://landregistry.data.gov.uk/app/ppd/.

If the proportion houses for which the selling price is above 1 mln

GPB is used as metric for the house values, no support is found for a

decrease in these values. After all the proportion with a selling price

above 1 mln GPB increased.

The average selling price decreased. It is not unexpected that the two

averages differ, because two more or less random groups are compared.

Actually it would be very surprising if the two averages would be

exactly the same. A lower mean selling price in January 2017, doesn’t

necessarily mean that the average value of all houses in the district in

January 2017 is lower than the average value in January 2016. The

question is whether this difference between the two means is merely a

matter of chance, or whether it is due to an underlying difference

between the values in January 2017 and in January 2016. To find out if

the difference is just a matter of chance, a so-called t-test can be

used. The conclusion would be that the outcome of a t-test does not

support the assumption that the mean value of houses in the city of

Westminster district in January 2017 (M = 1,478,800;

SD = 1,087,500) is less than in January 2016 (M =

1,490,100; SD = 999,000); t(566 ) = -.079; p

= 0.469.

Hypotheses testing the concepts

Hypotheses testing in court

In a trial there is a statement (hypothesis) the prosecutor wants to

prove: ‘the defendant is guilty’. As long as there is no evidence, the

opposite is accepted: ‘the defendant is not guilty’. The defendant is

found guilty only if the evidence that he is, is ‘beyond reasonable

doubt’. After the trial there are four possibilities:

1. The defendant is not guilty and is found not guilty (right

decision)

2. The defendant is not guilty, but is found guilty (wrong

decision)

3. The defendant is guilty but is not found guilty (wrong

decision)

(note: ‘not found guilty’ is not the same as found ‘not guilty’)

4. The defendant is guilty and is found guilty (right decision)

| WHAT IS REALLY TRUTH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| not guilty | guilty | ||

| DECISION | Acquitted | right decision |

wrong decision, second order error |

| Sentenced |

wrong decision, first order error |

right decision | |

Hypotheses testing in statistics

The principles for statistical testing of hypotheses are the same as these in court. The difference is that we are looking for statistical evidence instead of juridical. The researcher postulates a hypothesis he wants to prove, the so called HA (or H1) hypothesis. As long as there is no statistical evidence that this hypothesis is true, the opposite (the H0 hypothesis) is assumed to be true. After a testing procedure the researcher comes to the decision whether to reject or not reject the H0-hypothesis. In the same way as in court there are four possibilities, shown in the diagram below.

| WHAT IS REALLY TRUTH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| H0 is right | H0 is not right | ||

| DECISION | Do not reject H0 | right decision |

wrong decision, second order error (\(\beta\)-risk) |

| Reject H0 |

wrong decision, first order error (\(\alpha\)-risk) |

right decision | |

In a statistical procedure, we examine whether there is statistical

evidence that the data contradict the H0-hypothesis in favor

of the HA. If that is the case the H0-hypothesis

is rejected. Statistical evidence means that the \(\alpha\)-risk may not be greater than a

pre-agreed value (usually 0.05). If the statistical evidence is not

strong enough to reject the H0, we stay at the starting point

of the procedure (H0 is true) and we do not reject

H0. This does not mean that there is statistical evidence

that supports H0, it does mean that there is no statistical

reason to reject H0.

The way these statistical procedures are used in various statistical

tests is discussed in what follows.

Proportion tests or binomial tests

As can be seen in the above example (house values in London) it is sometimes possible to operationalize a research question by using proportions and formulate a hypothesis about these proportions.

Binomial Experiments

Experiments with two possible outcomes - often denoted as “Success”

and “Failure”” - are called Bernoulli experiments.

Repeating a Bernoulli experiment n times with the same probability p of

success for each attempt is called a binomial experiment.

Binomial test against a standard

In a univariate analysis a test against a standard is in many cases a good technique to operationalize a research question. Some examples.

Example: predicting the outcome of flipping a coin

(1)

Consider a person who claims to be clairvoyant (paranormal gifted) so

that he can predict the outcome of flipping a coin.1

Experiment: ask the person to predict the outcome if the coin is

flipped once.

Questions:

(i) If the predition is correct, would that be seen as support for the

claim?

(ii) What if the experiment is flipping the coin twice and both

predictions are correct?

(iii) What if the coin is flipped three times and all predictions are

correct?

(iv) After how many correct predictions can the claim be honored?

Example: predicting the outcome of flipping a coin

(2)

Consider a person who claims to be clairvoyant, and says he can better

predict the outcome of flipping a coin than simply by guessing. In other

words, the claim is that his predictions are correct in more than 50% of

the cases.

Research experiment (data collection): the person is asked to make 100

predictions. Based on the number of correct predictions (k) it will be

decided to honour his claim or not.

The hypothesis to test is HA: p > .5 where p is the

probability of a correct prediction. In the procedure we start with the

assumption that the claim is not correct, in other words p = .5. This is

called the H0-hypothesis.

The set of possible outcomes of the experiment are divided in two

groups. One group for which the H0-hypothesis is not rejected

and one group for which the H0-hypothesis is rejected in

favour of the HA-hypothesis. The last group is called the

Critical Region, because an outcome in this group can lead to a first

order error.

The partition in two groups is made so that the probability that a first

order error is made is at most a pre-determined value \(\alpha\), the significance level of the

test. The most common value used is \(\alpha\) = .05.

To come to a decision, that is to determine whether a test result

lies in the critical region or not, the so called prob-value will be

calculated, that is the probability to find a result as has been found,

or even further away from what is expected, assuming p = .5

(i.e. assuming H0 is true).

If this prob-value is low, than there are two options:

- the probability of a correct prediction is .5, the person was just

lucky in guessing correct a great number of times;

- the probability of a correct prediction is more than .5, and that is

why the predicted correct a great number of times.

If the prob-value is lower than the pre-agreed \(\alpha\) value the first option is rejected

and it is said that the data support the HA-hypothesis.

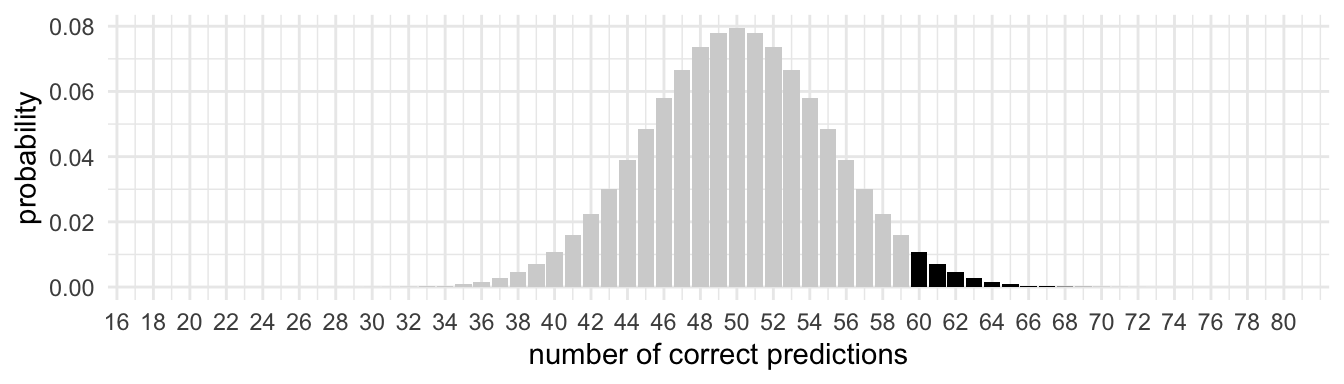

For instance if he predicts correctly 60 out of 100 times the prob-value equals 0.028. The prob-value has been calculated using the R function pbinom(). Another way to calculate this prob_value is by writing code to simulate the experiment assuming H0 is true, repeat this simulations many times (e.g. 10,000) and calculate the proportion of times that 60 or more simulated guesses out of 100 are correct. See the R script

Figure 9.2

Binomial distribution with n = 100, p = .50

n <- 100

k <- 0:100

p <- 0.5

probs <- dbinom(x = k, size = n, prob = p)

df <- data.frame(k, probs)

ggplot(df, aes(k, probs)) +

geom_bar(data = df[20:60, ], stat = "identity", fill = "lightgrey") +

geom_bar(data = df[61:80, ], stat = "identity", fill = "black") +

theme_minimal() +

xlab("number of correct predictions") +

ylab("probability") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(0,80,2))

Note. The black area corresponds with the probability of 60 or more successes in 100 trials under the assumption that a probability of a success equals 0.50.

Example: filling packages of sugar

Packs of sugar are filled using a filling machine. Although on average

the contents is 1000 gram there is always some variation in the contents

of the packs of sugar. In the past 10% of the packages contain less than

995 grams. This was reason to buy a new packing machine. To test if this

machine performs better than the old one, a random sample of 100 packs

is drawn. From these packs, 6 contain less than 995 grams. Does this

sample result give statistical evidence that the machine performs

better? In other words: is this sample result enough evidence that in

the population less than 10% of the packages contain less than 995

grams.

To answer this question we assume the null-hypothesis - H0: 10% of the packages contain less than 995 grams - to be true and calculate the probability to find 6 or less packs with less than 995 grams under this assumption.

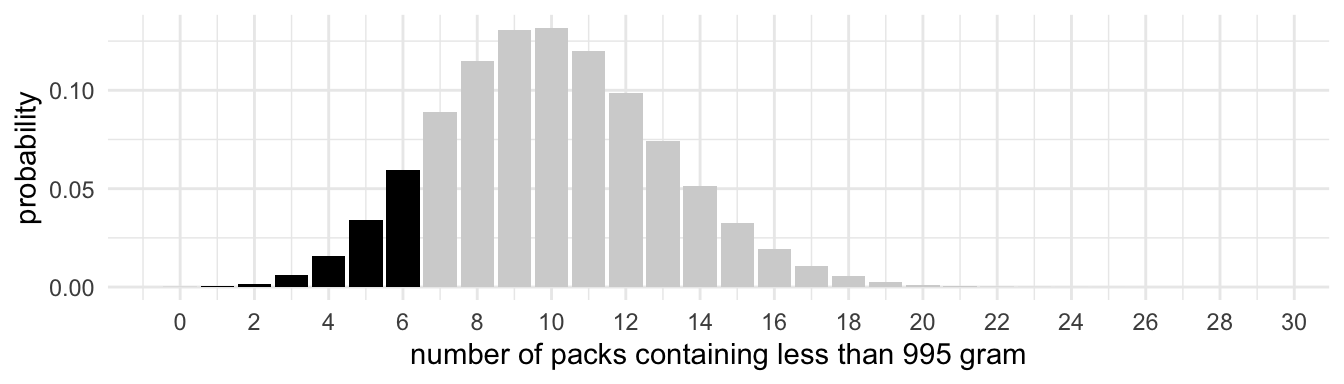

Figure 3

Binomial distribution with n = 100, p = .10

n <- 100

k <- 0:100

p <- 0.1

probs <- dbinom(x = k, size = n, prob = p)

df <- data.frame(k, probs)

ggplot(df, aes(k, probs)) +

geom_bar(data = df[1:7, ], stat = "identity", fill = "black") +

geom_bar(data = df[8:30, ], stat = "identity", fill = "lightgrey") +

theme_minimal() +

xlab("number of packs containing less than 995 gram") +

ylab("probability") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(0,30,2))

The black area corresponds with the probability of 6 or less successes in 100 trials under the assumption that the probability of a success equals 0.10.

The prob-value in this case equals .117. In other words, at a .05 significance level, the data do not support the hypothesis that less than 10% op the packs contain less than 995 grams. So the data do not give support to the hypothesis that the new machine is better. This does not mean that the new machine is not better than the old one; it does say that the collected data do not give ‘statistical evidence’ that the new machine is better.

Question: for which numbers of packages in the sample that contain less than 995 gram, would the H0-hypothesis be rejected?

Note that if the data is expanded the conclusion can change. E.g. if n = 200 and k = 12 the result would be significant (prob-value = .032).

Writing it up

Scientific reports use a standard for many aspects of the report,

among which referencing, format for tables and figures and formatting

text. A commonly used style is APA style, see this

webpage.

APA style also applies to reporting results of hypothesis testing.

In the last example the result can be reported as follows.

Based on a one-sided binomial test the observed values (N =

100, K = 6) do not give significant support to the assumption

that less than 10 percent of the packages filled by this machine,

contain less than 1000 grams, p = .117.

Proportion test: comparing two groups

In a statistical analysis it is quite common to compare different

groups. For instance the differences between incomes in the profit and

the not-for-profit sector, the air quality in different cities, and so

on.

Comparing proportions in two different groups can sometimes be used to

operationalize a research question about differences between two

groups.

Example: influence website background on users

In an experiment data is collected about the influence of background

colors on the attractiveness of a website. Attractiveness has been

operationalized by the proportion of visitors that click on a button for

more information.

The same information was presented on two different backgrounds (I and

II). From former research it was expected that website I is more

attractive than website II.

Data collected: of the 250 visitors to the website with background I, 40

have pressed a click button to get more information; of the 225 visitors

to the website with background II, 25 pressed the button.

The question is whether this data support the hypothesis that background

I is more attractive.

In a statistical sence, the hypothesis to be tested is:

HA: pI > pII; where p1 is

the proportion visitors of website I that clicks on the button and

pII the proportion of website II that clicks on this

button.

This is an example of a two sample proportion test.

To find out if the data support the HA-hypothesis, the

probability is calculated that assuming H0 is true, a

difference between the two proportions will be found as has been found

in the collected data.2 THe p-value can be calculated with R’s

prop.test() function:

p-value = prop.test(x=c(40,25), n=c(250,225), alternative = “greater”).

The conclusion would be: a one-sided two-independent-samples

proportion test did not support the assumptiom that visitors of website

I significantly more often click the button (N = 250,

K = 40, proportion = .160) than visitors of website II

do (N = 225, K = 25, proportion = .111),

p = .079.

The mathematical background behind this calculation is based on the distribution of all possible differences between p1 and p2 in two samples, under the assumption that in real the two proportions are the same. Under the condition that the sample sizes are not too small, this distribution is a normal distribution.↩︎